Marengo

Marengo is a history student from Amsterdam with a special interest in Portuguese, Napoleonic and Dutch royals.

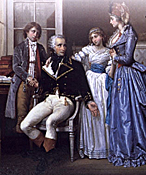

View all articles by Marengo Hortense was the second child of Marquis Alexandre de Beauharnais (pictured at left with his family) and Rose Tascher de la Pagerie (later known as Josephine). Her parents did not meet until after their wedding contract had been signed by their families. Their first meeting took place in the port of Brest, where Rose arrived in France from her home in the French colony of Martinique. She was born and raised in Martinique by her parents, impoverished French nobles, and thus was considered a Creole. Creoles were looked down on in the Parisian salons during the reign of Louis XVI because of their lethargy, ignorance, and gaucheness. The marriage, not surprisingly, was a failure from the start. Alexandre never really warmed to his wife, and he even seemed somewhat embarrassed by her.

Hortense was the second child of Marquis Alexandre de Beauharnais (pictured at left with his family) and Rose Tascher de la Pagerie (later known as Josephine). Her parents did not meet until after their wedding contract had been signed by their families. Their first meeting took place in the port of Brest, where Rose arrived in France from her home in the French colony of Martinique. She was born and raised in Martinique by her parents, impoverished French nobles, and thus was considered a Creole. Creoles were looked down on in the Parisian salons during the reign of Louis XVI because of their lethargy, ignorance, and gaucheness. The marriage, not surprisingly, was a failure from the start. Alexandre never really warmed to his wife, and he even seemed somewhat embarrassed by her. After the birth of their son Eugène, Rose de Beauharnais became pregnant by a brief and loveless second 'embrace'. Alexandre refused to believe that he was the father of the small girl named Hortense, born on 10 April 1783, and demanded a divorce. Rose was required to withdraw into a convent, where she found herself in the company of women who had suffered the same fate. She stayed in the convent for 15 months, learning aristocratic manners from the other women there. After her divorce was settled, she went back to Martinique to live with her mother. She took her daughter Hortense (pictured at right) with her, but she had to leave her son Eugène in the care of his father and paternal grandparents. This separation must have been a traumatic experience for the two children, as they were each other's best friends. Thus, Hortense spent much of her childhood at the plantation of her grandmother on Martinique. With her curly blond hair and blue eyes, she was much admired by the black slaves, and she was delighted by their rhythmic dancing and songs. Here Hortense developed the talent to enjoy music and dancing in a free manner.

After the birth of their son Eugène, Rose de Beauharnais became pregnant by a brief and loveless second 'embrace'. Alexandre refused to believe that he was the father of the small girl named Hortense, born on 10 April 1783, and demanded a divorce. Rose was required to withdraw into a convent, where she found herself in the company of women who had suffered the same fate. She stayed in the convent for 15 months, learning aristocratic manners from the other women there. After her divorce was settled, she went back to Martinique to live with her mother. She took her daughter Hortense (pictured at right) with her, but she had to leave her son Eugène in the care of his father and paternal grandparents. This separation must have been a traumatic experience for the two children, as they were each other's best friends. Thus, Hortense spent much of her childhood at the plantation of her grandmother on Martinique. With her curly blond hair and blue eyes, she was much admired by the black slaves, and she was delighted by their rhythmic dancing and songs. Here Hortense developed the talent to enjoy music and dancing in a free manner.Her stepfather Napoleon would later admire this quality and describe her as "nôtre Terpsichore."

Adolescent Years

At the start of a slave insurrection, Rose and her daughter hastily escaped Martinique and sailed to Paris, where the French revolution had put an end to the reign of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette (both ended up on the scaffold). In the hell of the "terror," Hortense's noble father and mother were taken prisoner. Hortense and her brother Eugène were reduced to wandering through the streets of Paris, helped by their governess, the Belgian Countess de Lannoy. Alexandre de Beauharnais was one of many thousands who met their death under the guillotine. But shortly before Rose met the same fate, she was released from prison because of her contacts with the new regime that had overthrown Robespierre. Now, however, she was a widow with two small children, penniless and alone on the streets.

To forget the horrors of the revolution and to enjoy herself as much as possible, the widow embraced Parisian society and quickly befriended some influential people. Hortense was sent off to a boarding school for girls, run by Madame Campan in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Here she received an excellent education: she learned to make music and, besides the usual skills such as learning languages, took dancing and acting lessons. She received painting and drawing lessons from the famous Jean Baptiste Isabey. Hortense excelled in everything and was loved by everyone at school. But her mother had no time to admire her daughter. Rose used all her charms and the aristocratic manners learned from the ladies in the convent to get into the good graces of the new establishment. She dressed extravagantly, spared no expense in the decoration and furnishing of her rented house, and looked for rich lovers who could pay off her debts. One day she presented her daughter during a dinner party to an intensely pale Corsican general: Napoleon Bonaparte (pictured above with Josephine and Hortense). Hortense could not stand him and made no secret of her dislike. The 28-year-old general changed the name of his 32-year-old bride-to-be from Rose to Josephine, and from now on he made the decisions about their lives. Without informing Hortense and Eugène, the couple quickly married. While Napoleon was on a military expedition to Italy, where he gained one victory after another, he tried to get into his stepdaughter's good graces by presenting her with one present after another: perfumes, watches, jewels, and letters. But Hortense was still angry because Napoleon had stolen the heart of her mother and answered him in a cold tone. Napoléon wrote back: "I have received your friendly note ... you are a naughty, a very naughty little girl! ... and then, something which you know perfectly well, your mother can not be compared to any other woman in the world ... when it would be allowed to enlarge her happiness, I would consider it as one of my sweet duties, which I have now towards you. I will feel for you like a father and you will love me like your best friend." After these words Hortense slowly softened her attitude toward the general.

To forget the horrors of the revolution and to enjoy herself as much as possible, the widow embraced Parisian society and quickly befriended some influential people. Hortense was sent off to a boarding school for girls, run by Madame Campan in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Here she received an excellent education: she learned to make music and, besides the usual skills such as learning languages, took dancing and acting lessons. She received painting and drawing lessons from the famous Jean Baptiste Isabey. Hortense excelled in everything and was loved by everyone at school. But her mother had no time to admire her daughter. Rose used all her charms and the aristocratic manners learned from the ladies in the convent to get into the good graces of the new establishment. She dressed extravagantly, spared no expense in the decoration and furnishing of her rented house, and looked for rich lovers who could pay off her debts. One day she presented her daughter during a dinner party to an intensely pale Corsican general: Napoleon Bonaparte (pictured above with Josephine and Hortense). Hortense could not stand him and made no secret of her dislike. The 28-year-old general changed the name of his 32-year-old bride-to-be from Rose to Josephine, and from now on he made the decisions about their lives. Without informing Hortense and Eugène, the couple quickly married. While Napoleon was on a military expedition to Italy, where he gained one victory after another, he tried to get into his stepdaughter's good graces by presenting her with one present after another: perfumes, watches, jewels, and letters. But Hortense was still angry because Napoleon had stolen the heart of her mother and answered him in a cold tone. Napoléon wrote back: "I have received your friendly note ... you are a naughty, a very naughty little girl! ... and then, something which you know perfectly well, your mother can not be compared to any other woman in the world ... when it would be allowed to enlarge her happiness, I would consider it as one of my sweet duties, which I have now towards you. I will feel for you like a father and you will love me like your best friend." After these words Hortense slowly softened her attitude toward the general.

Napoleon's star was rising quickly. He returned from Italy in triumph and quickly left again with his troops and went to Egypt. On his return to Paris in 1799 he staged a coup and overthrew the rule of the Directorate. He raised himself to be a Consul and later to be the First Consul of the French Republic. In this role he had almost royal powers. Josephine moved with Napoleon from their house on the Rue de la Victoire to the Palais du Luxembourg and later to the Tuileries. Much against her own will, Hortense was asked to come home from her school frequently, in order to attend lavish banquets, balls, and receptions. She became part of the sparkling company around Napoleon, which quickly took on the character of a royal court. The family of the First Consul spent their weekends at Château Malmaison. Mother and daughter became inseparable and endlessly discussed interior decorations, the garden layout, and purchases of artworks, all to enhance Malmaison. Josephine was insatiable in buying paintings by, among others, Girodet, Gérard, David, Isabey, and Gros. From the Italian sculptor Canova she bought elegant sculptures. She had fairy-like gardens made with glasshouses, in which she grew exotic flowers. To give Hortense the chance to develop her passion for the stage, Josephine had a theatre built where Hortense received applause for her ballets and her acting. Hortense also played the pianoforte and the harp. Later she arranged large court ballets at the Tuileries, which delighted Parisian society.

When Hortense became old enough to marry, Josephine suggested that she marry Louis Bonaparte, the younger brother of Napoleon. In their children the blood of Napoleon and that of Josephine would be united. Josephine hoped to save her own position this way because she was unable to give her husband any children and was afraid that Napoleon might divorce her for that reason. Hortense was shocked; she was in love with somebody else and disliked the sombre Louis, who annoyed her with his eternal complaining. But Hortense was eager to please her mother and, against her own better judgement, married Louis Bonaparte. Louis was not attracted to Hortense either, but he also did what his elder brother wanted and went ahead with the marriage. In January 1802 the inescapable and unfortunate marriage took place. Nine months later Hortense gave birth to her first child, a boy; the child's step-grandfather decided that he would be named Napoleon Charles Bonaparte. Josephine rejoiced; her position at the side of the First Consul now seemed secure.

When Hortense became old enough to marry, Josephine suggested that she marry Louis Bonaparte, the younger brother of Napoleon. In their children the blood of Napoleon and that of Josephine would be united. Josephine hoped to save her own position this way because she was unable to give her husband any children and was afraid that Napoleon might divorce her for that reason. Hortense was shocked; she was in love with somebody else and disliked the sombre Louis, who annoyed her with his eternal complaining. But Hortense was eager to please her mother and, against her own better judgement, married Louis Bonaparte. Louis was not attracted to Hortense either, but he also did what his elder brother wanted and went ahead with the marriage. In January 1802 the inescapable and unfortunate marriage took place. Nine months later Hortense gave birth to her first child, a boy; the child's step-grandfather decided that he would be named Napoleon Charles Bonaparte. Josephine rejoiced; her position at the side of the First Consul now seemed secure.

Louis Bonaparte, Napoleon's brother and Hortense's husband