- Home

- Monarchy Today

- Can This Monarchy Be Saved?

Can This Monarchy Be Saved?

- By Dana Duke

- Published 05/14/2008

- Monarchy Today

Dana Duke

Dana Duke is a corporate trainer living in New York with interests in Europe, royalty, reading, and biking. Her username at TRF is ysbel.

View all articles by Dana DukeQueen in People's Hearts

When Diana gave her famous Panorama interview and said that she knew that she would never be Queen of this country but she wanted to be Queen in People’s Hearts, I wasn’t shocked. Diana had always said she let her heart rule her head, and so it was obvious that given a choice between a crown bestowed by rites and tradition and a crown bestowed by the love of the people, she would choose to be crowned in people’s hearts. I thought the crown bestowed by rites and tradition and a sense of continuity was just as important and if Diana wanted to be Queen in People's Hearts, then Elizabeth II could go on being Queen of the country.

However, my good friend and fellow Royal Forums member Elspeth was aghast by Diana’s wish to become Queen in People’s Hearts, saying that in a constitutional monarchy, the Queen is queen in people's hearts or she's in deep trouble, because that's the source of her legitimacy as Queen. That got me to wondering about the relationship between the British people and the royal family before Diana.

As a young girl, I used to dream about visiting other countries and would indulge those fantasies by reading about them in my World Book Encyclopedia, an American encyclopedia that was a little less scholarly and a little more accessible for a seven-year-old girl than the august Encyclopaedia Britannica. The British Isles seemed a magical land (although I must confess that at that age I still believed that Ireland and England were one and the same and that as America's mother country, England was far larger than the United States; I also believed that leprechauns were dancing in Ireland - I asked my neighbor after he’d been on a business trip if he’d seen one and if everything in the country was really green). England seemed full of hearty fellows who drank pints in pubs, where it was always raining, but where everyone was always cheerful. The Brits seemed to value their way of life and be confident in it no matter what. They had a Queen and a royal family, which we didn’t have in America and which I thought was strange, but they seemed to love their royal family anyway. My World Book Encyclopedia said about the average Briton that he “cares deeply about the Royal Family and holds them close to his heart." Notice that the encyclopedia didn’t state that the British held the royal family close in their minds. Americans would playfully poke fun at their British friends about the British loyalty to the royal family. In one episode of the original Mickey Mouse Club, where one of the Mouseketeers visited a boy in England, he joked about good old Charlie having a lot of space in the palace to lay out tracks for his toy trains (referring to Prince Charles, who must have been around 10 years old at the time) and the British boy got charmingly put out and said, "He is our future King so I wish you would refer to him as His Royal Highness Prince Charles." The American boy just laughed and said, "That’s nothing, back home we call him Chuck."

I used to think that the British people had chosen this rather odd form of government, where the person of the monarch occupied its highest pedestal, for good, commonsense reasons: because a person who had no political influence could represent the whole country better than a politician, who at his most popular would have been elected by less than 100% of the population. But now I think the British chose the crown less from an appeal to reason than from an appeal to the heart. The royal family had always been there - comfortable and familiar. It seemed more personal to pledge allegiance to a King or Queen rather than to an impersonal flag as we in America preferred to do. The Brits, it seems, wanted a person to be loyal to, someone to devote their lives to, someone to sing God Save the Queen to, someone to fight for and defend, and, in cases of dire need, someone to die for as soldiers in wars past have devoted their lives "to King and Country." They wanted a royal family that they could care about. They didn’t judge the royals by how much money they spent or the number of duties they completed in a year or how hard they worked (everybody knew that the Queen Mother spent oodles and oodles of money, but that did not detract from their loyalty to her). The Royal Family showed their worth by their very existence - they were a symbol for the nation and not a family of clock punchers for the nation.

Yes, people knew that the Queen Mother could be ruthless underneath her exterior of wisteria and hyacinth. They knew that Charles was hopelessly fuddy-duddy and a little bit pompous, expecting even his close friends to call him Sir; and they knew that Margaret was wild and could be very rude. They knew that Anne and Andrew could be hot-tempered and treated their servants badly. And that Philip thought the Chinese had slitty eyes. They also knew that the Queen was not going to do anything about it. But despite all this, the Brits didn’t care; this was their family, and with family you accept them and defend them, warts and all, the way you would defend your own family to an outsider even though privately you may harbor reservations about them. In the preparations for the Queen's visit to America during the Bicentennial of 1976, I remember an article in the Ladies' Home Journal written by an American journalist who had tried and failed to write a daring exposé of the British royal family. She wrote that she was dumbfounded how deeply entrenched the loyalty to the royal family was in Britain and complained that whenever she wanted to get some dirt on one member of the family or another (mostly Princess Anne), she was told, "no we only want to read nice stories about the Queen and her family; if there is anything unsavoury, we don’t want to read it."

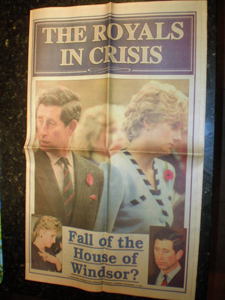

Diana versus the Windsors

Yet something changed when Diana came on the scene. At the beginning it seemed that in the fairytale romance, people were just making some extra space in their hearts for Diana where the royal family already reigned. Yes, people knew Diana was young, yes they knew she was very innocent and inexperienced, and a few people grumbled about why only a virgin from an aristocratic background was considered suitable as a bride for the future King of England. But most people calmly and confidently waved away these misgivings. Of course only a virgin would be suitable; their royal family only deserved the purest of brides, and with Diana’s gentle and submissive nature she would always support her husband and his family and would never go against them. Because what was most important to the British royal family, and without which they couldn’t survive, was loyalty. Her family, the Spencers, were championed as being one of the few old aristocratic families that had never rebelled against the crown, and one story of their loyalty to the crown was of a famous argument in Parliament between the first titled peer in the family, Baron Spencer of Wormleighton, and the Earl of Arundel, heir to the great Duke of Norfolk and the pre-eminent peer in the land. The new noble made his appearance in the House of Lords and promptly began giving advice on the conduct of the government. The august Earl of Arundel thanked the new Baron for his suggestions and reminded him that while the ancestors of the other men present were dying in battle for the glory of the nation, the sheep-grazing Spencers of Warwickshire had amounted to absolutely nothing. Lord Spencer is reported to have answered, "When my ancestors were, as you say, keeping sheep, yours, my lord, were plotting treason." The people were assured that the Spencers were ever loyal, ever trusted servants of the Crown, and so a daughter of their blood and their fine upbringing was the perfect candidate to become Charles’ Queen and help the royal family remain in people’s hearts.

It appeared at first that she definitely did help the royal family to remain in people's hearts. Even in America, where people were often cynical about royals, the popular magazine Newsweek put Charles and Diana on the cover with a simple headline of "Good Show." In truth, not all the coverage was positive. However, the difference in the early years was that, regardless of whether the press was positive or negative, Charles and Diana were seen as a unit. So if either of them received praise, it reflected on the other and the whole royal family. On the other hand, if either of them received censure, that also reflected on their partner and the whole family. Good or bad, Charles, Diana, and the royal family were all thought of as one.

At some point, that began to change. There were stories of Diana’s warmth and success when meeting groups of people, and some people began to talk openly of how they were disappointed to see Charles at some events when they had expected to see Diana. The image of Diana as the perfect fairytale princess within the whole package of the British royal family was replaced by the image of Diana as a fairytale princess in her own right without the royal family. She became a fashion icon for some, an idealized young wife and mother for others, a champion of the underprivileged for yet others. Regardless of why people loved Diana, the family she married into seemed to become less and less important.

At some point, that began to change. There were stories of Diana’s warmth and success when meeting groups of people, and some people began to talk openly of how they were disappointed to see Charles at some events when they had expected to see Diana. The image of Diana as the perfect fairytale princess within the whole package of the British royal family was replaced by the image of Diana as a fairytale princess in her own right without the royal family. She became a fashion icon for some, an idealized young wife and mother for others, a champion of the underprivileged for yet others. Regardless of why people loved Diana, the family she married into seemed to become less and less important.

Someone once mused that it was unfortunate that Charles didn’t let Diana take the spotlight and accept a supporting role in the same way that President Kennedy had glowed in the admiration that the world held for his First Lady, Jacqueline Kennedy. The reason for this I believe goes back to the purpose of the royal family and how it is different from the role of the President of the United States. Kennedy was not only Head of State but also head of the government; if Jackie took the center stage from him in the arena of glamour and style, then Jack knew he could banish her from his secret Cabinet meetings, the Cuban missile crisis, his campaign to put the first man on the Moon. As President of the United States and head of the government as well as Head of State, Jack Kennedy had a very distinct and important role as the leader of the country and the one whose actions and decisions could influence a whole nation. While Charles will be Head of State, he will never be head of the government; if his wife replaces him in people’s hearts, in a way he has failed in the role of the heir to the British throne. When Jack Kennedy said something about being the man who accompanied Jackie Kennedy to Paris, people knew he was joking, and the only reason that the joke was funny was that the people knew it wasn't the truth - no matter how stylish and captivating Jackie was, she could never take Jack's place in the governing of the country. When Charles made a similar joke about Diana, it wasn't funny because it came too close to the truth.

In the meantime, Diana seemed to benefit from the people’s willingness to overlook anything negative about her in the same way the people had overlooked the negatives of the royal family a decade earlier. They now overlooked or made innocent explanations for increasing signs of Diana’s instability in the same way that, a decade before, they had made excuses for Philip’s racist comments and the Queen Mother’s overspending ways. They saw Diana as one of them, and naturally you defend one of your own, no matter what she's done. If loyalties had remained like this, the way they were in the few years after the wedding when the marriage was hopelessly lost but the public didn’t know it yet, then I think the royal family would have muddled through for a while, becoming the supporting cast for the Princess of Wales. They could have been totally dependent upon her popularity and the goodwill of the people for their own existence, which could have bought them some time in the short run but which wouldn't have provided a stable platform for them in the long term.

Diana Triumphant?

But the hearts of the British public were changing yet further. The first signs of this new relationship between the British people and the royal family came when elements in the press, and two reporters in particular, appeared to throw down the gauntlet and take up the challenge as the champions and knights in shining armour of the Princess of Wales against the royal family. These two reporters, James Whittaker and Andrew Morton, later claimed that they started to defend the Princess of Wales because they didn’t like the hints from the Prince of Wales’ office that Diana was unstable. Richard Kay seemed to pick up the gauntlet later. This was the start of the War of the Waleses, where the Prince and Princess of Wales were fighting for a place in the hearts of the people. A few people were disgusted with both of them for an unseemly display of one-upmanship, plots, and leaks, but the majority of people fell into camps on either side, and we shouldn’t be surprised. After all, the appeal of the royal family had always been that it was the family for whom normal everyday Brits would defend and lay down their lives if necessary because it represented the best of all that the British saw in themselves. If someone, even someone who had married into the royal family, appeared even innocently to challenge the rest of the family for this loyalty, then it was unavoidable that the nation would take sides because loyalty has never been a matter of the mind but one of the heart and in order to remain loyal to either the royal family or Diana required some to set aside some misgivings of the mind.

The two main pieces of ammunition Diana lobbed against the royal family were the Andrew Morton book and the Panorama interview. In the time between the two Diana met with members of the press and directly appealed to them to report favorably on her. The ammunition Charles lobbed was the Dimbleby book and interview. People’s loyalties were revealed by which outraged them more. Was it Charles’ public acknowledgement that he had been unfaithful, or was it Diana’s suggestion that Charles go somewhere far away with his lady friend and leave Diana to raise her boys alone? Which one did you simply find misguided, and which one did you find heartless and inexcusable? Your answers to this question determined where your loyalties but, more importantly, where your heart lay.

And for most people, Diana most decidedly won this battle. I’m not so interested in exploring why she won or whether it was right that she won. What’s important to note is that she did win. But in the process, what was won and what was lost? The unsatisfying part of the whole saga for those who cared about all of this is that despite her public relations triumph, Diana did not appear to win out for herself in the end. After her divorce in 1996, she died only a year later in a needless car crash with a man she barely knew. Her fans tried to put a positive spin on the last months of her life. Diana was coming into her own, they said; she was the strongest that she had been in decades. However, her decision as the most famous and beloved woman in the world to forego security, doubts that the main reason that she was in the relationship with Dodi al-Fayed was to either embarrass the royal family or to make a former boyfriend (Hasnat Khan) jealous – these thoughts, which would not go away, really made it harder to believe that her life at its end was a success story.

Yet in Diana’s death, did the royal family come out a winner? Sadly not, if you look at reader responses to the BBC's Have Your Say or the other news outlets. Now every time the Queen makes a speech or a royal dies, as did Princess Alice a few years ago, invariably there will be quite a few complaining that the royals are a waste of space or useless and berating the BBC for giving airtime to this claptrap. The unkindest cut of all is when someone mentions that Diana was of course crazy and off her rocker and that no one should be as immune to criticism as she was in life, and then they mention, as an aside, that the family she married into was even worse than she was. It seems that Diana had damaged the royal family in addition to her own legacy.

Yet in Diana’s death, did the royal family come out a winner? Sadly not, if you look at reader responses to the BBC's Have Your Say or the other news outlets. Now every time the Queen makes a speech or a royal dies, as did Princess Alice a few years ago, invariably there will be quite a few complaining that the royals are a waste of space or useless and berating the BBC for giving airtime to this claptrap. The unkindest cut of all is when someone mentions that Diana was of course crazy and off her rocker and that no one should be as immune to criticism as she was in life, and then they mention, as an aside, that the family she married into was even worse than she was. It seems that Diana had damaged the royal family in addition to her own legacy.

Of course Charles had by this time lost any Teflon he had ever had. His elders decried him for being weak for not standing up to his father and opposing the marriage in the first place; women hated him for being cruel for not understanding and supporting Diana’s emotional problems and selfish for seeking his own comfort with Camilla while leaving his wife alone and lonely; and other men actually ridiculed him for not choosing a mistress who was younger and prettier than Diana, for in their opinion that would have been the only reason to have a mistress. If people did not fault him for these things, then they faulted him for not having better public relations and letting his wife beat up on him in public.

But the rest of the royal family took a beating too. Even Margaret and Anne were berated for being cold towards Diana, when in truth they were so busy with their own lives that they didn't have time to mess with Charles'. But for the first time, the Queen was criticized. She was censured for not siding with Diana against Charles and making Charles send Camilla away. Because Diana had already replaced the Queen in people’s hearts, no one questioned the wisdom of a daughter-in-law asking her mother-in-law to side with her against the Queen's firstborn son, whom she had given birth to at the young age of 21. No one seriously considered whether Diana would have sided with a future daughter-in-law against her own firstborn son if William had acted in a similar way to his father. But the important point was that nobody cared about the difficulties that the Queen felt, they only cared about Diana getting hurt.

If there had been any doubt that the Queen had lost her place in people’s hearts, one needed to look no further than the angry crowds outside Buckingham Palace after Diana died, when the Queen did not return from Balmoral promptly enough for the public’s satisfaction to show respect to the woman they had crowned as their Queen – Diana. Her Majesty was seen as an impediment and a disgrace to those who wanted the world to show homage to Diana, and the Queen’s personal feelings didn’t matter. During her life, however, Diana's feelings did matter, for if they were hurt in anyway by anyone that was a sin that was not forgivable. This reaction was considered natural, for this anger on her behalf, this outrage at any injustice done, is generally the right and privilege of the woman who has been crowned the Queen of People’s Hearts. The Queen had occupied that lofty pedestal for her people at one time, and they would have been just as angry with anyone who affronted her dignity as they later were on Diana's behalf. However, that time had passed. If you doubt that, I invite you to ask yourself whose hurt made you most angry when you saw it: Diana’s or Elizabeth's? That was the queen who captured your heart and the heart never lies.