- Home

- General Interest

- Royal Death

Royal Death

- By BeatrixFan

- Published 06/14/2008

- General Interest

BeatrixFan

BeatrixFan is an English drag queen with an unhealthy obsession with big hair. He has been a forum member for four years and has a special passion for the Duchess of Cornwall. Totally unreciprocated of course.

Whether you’re a devotee of the surgeon’s knife or whether you’re resigned to growing old gracefully, there’s something even more inevitable than wrinkles – death. It comes to us all, but it remains one of the world’s little quirks that despite ending up in the same waxy position as a pauper, if you’re a Prince in life so shall you depart in regal style. Royalty has adopted its own customs for seeing off its stiff Dukes and Duchesses which makes the final Tube journey on the Underground of existence as imperious as possible. Not only do the mourners have the responsibility to look dignified during the grand procession favoured by European royals, but the corpse has to behave itself both before and after. Before croaking, a tongue-in-cheek quip that can make many a dinner table roar with affectionate laughter is in order. Edward VII chose to acknowledge the results of the 4.15 at Kempton (after bidding farewell to his wife and his mistress, seated side by side at his bedside), while Madame de Pompadour applied a lashing of rouge before breathing her last. After the individual in question dies, the ceremonial begins, and it is here, my dear readers, that variety is most definitely the spice of death. In Europe, the descendants of Victoria and Christian flock in their droves like well-heeled lambs to churches. In the Far East, most exotic rituals are undertaken with ancient splendour revived. The death of the Maori queen in 2006 was an occasion for ceremony and ritual, although it involved bare-chested warriors instead of soldiers in uniform, a woven mat instead of a Royal Standard draped over the coffin, and a journey in a canoe instead of a procession through the streets on a gun carriage or a hearse.

Pharaohs

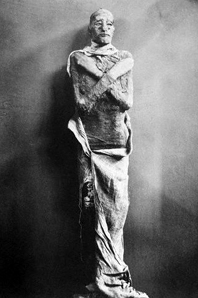

Ironically, death was the most important part of Egyptian life and something that was prepared for over many years, with the building of a Pharaoh's tomb which started the moment he became King. The rituals surrounding royal death in Ancient Egypt have given the world some of its most inspiring stories, amazing architecture, and luxurious riches. Pharaohs gave a new meaning to the word tomb, and in much the same way as the Ancient Chinese Emperors were buried, death was seen as an extension to life but they also believed that the body was somehow used as a vehicle into the next world and so not only preserved it but filled the tomb with practical items such as new clothes, jewellery, wines, chariots, shoes, weapons, furs, silks, and money. This belief was responsible for the terracotta army, a staggeringly complex multitude of clay figures cast for the tomb of the first Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huangdi. His companions included not only warriors to help him conquer new realms in the afterlife but also hundreds of bureaucrats and court officials to make his reincarnation as wealthy as his life. The Ancient Egyptians didn't believe in reincarnation, but they did believe in the importance of preserving a body, and so was born the art of mummification (impressively exemplified by Ramses III [pictured at left]). For those who are squeamish, go and pour a pink gin now.

Ironically, death was the most important part of Egyptian life and something that was prepared for over many years, with the building of a Pharaoh's tomb which started the moment he became King. The rituals surrounding royal death in Ancient Egypt have given the world some of its most inspiring stories, amazing architecture, and luxurious riches. Pharaohs gave a new meaning to the word tomb, and in much the same way as the Ancient Chinese Emperors were buried, death was seen as an extension to life but they also believed that the body was somehow used as a vehicle into the next world and so not only preserved it but filled the tomb with practical items such as new clothes, jewellery, wines, chariots, shoes, weapons, furs, silks, and money. This belief was responsible for the terracotta army, a staggeringly complex multitude of clay figures cast for the tomb of the first Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huangdi. His companions included not only warriors to help him conquer new realms in the afterlife but also hundreds of bureaucrats and court officials to make his reincarnation as wealthy as his life. The Ancient Egyptians didn't believe in reincarnation, but they did believe in the importance of preserving a body, and so was born the art of mummification (impressively exemplified by Ramses III [pictured at left]). For those who are squeamish, go and pour a pink gin now.

It was believed that the soul of a dead Pharaoh would live on in his body before being liberated by the Gods. The intense heat of Egypt generally caused bodies to decompose within a matter of hours, and so the ancients developed mummification, the art of preservation. Little did they know that their technique would mean that even today, nearly 2000 years later, mummies are still being unearthed intact. The Pharaoh would be laid on a board and the abdomen opened so that the internal organs could be removed and placed in canopic jars. These went with the Pharaoh into his tomb, and it was believed that the theft or loss of these jars preventing one entering the afterlife as one would be incomplete. Lungs, liver, intestines, and stomach were placed into special containers with the hope that they'd survive, but in all those found, the organs haven't survived. Bones in the cranium were then smashed and the brain pulped with a rod before being pulled through the nose and discarded. After cleaning, the head cavity was filled with resin and the other cavities were packed with a type of salt which removed any liquids from the body. Moisture causes decomposition, and over 40 days, the body was completely dried. Then it would be wrapped in bandages and placed in a sarcophagus, ready to be buried in the Valley of the Kings.

The famous Book of the Dead actually consisted of funeral ceremonies used by royal priests and was kept for only the highest in Egyptian society, but as time went on, the knowledge became available to all and priests learned the ceremonies diligently to ensure a swift passage into the great beyond. Tombs were considered sacred and robbery was uncommon - until modern man arrived on the scene and pillaged away until his museums were as full as they could be. Even the bodies of the Pharaohs are now subjected to CAT scans and carbon dating to determine identity and age. Some may call it Egyptology; the ancients would probably be more realistic and label it grave robbing and desecration.

Popes

Perhaps the most intense ritual surrounding the death of a monarch is seen in the Papal Monarchy, for when a Pope dies the eyes of the world turn to the Vatican as they not only prepare to select a new Pontiff but carefully and reverently send the old one off on his final journey. Luckily, the Cardinals aren't left wondering what to do, because the Apostolic Constitution spells out in clearest Latin what must be done. In the past, the death of a Pope and the subsequent funeral arrangements were pretty much unknown until they had been and gone. Nowadays, the last moments of a Pope's life are relayed breath by breath to the billions of Catholics who look to the Pope as God's representative on Earth, but the ceremony surrounding the death hasn't changed for centuries.

When the doctor declares the Pope to be medically dead, the Camerlengo of the Church (a kind of Lord Chancellor) is charged with confirming the event. He takes a small silver hammer and gently taps the Pope on the head with it three times, calling the Pope's birth name and not his regnal name. If the Pope doesn't jump up and say, "Hit me with that hammer once more and I'll bash your teeth in," he is clearly dead, and immediately the people who were with him at the time of his death move out of the Papal Apartments, which are then sealed with candle wax and yellow and white ribbon. They are unsealed by his successor. The Cardinal Vicar of the Diocese of Rome then tells the world the Pope has died and the circumstances surrounding that death. Then begins the controversial ritual of embalming.

The Pharaohs were mummified, and though there are specialist companies that will gladly perform a mummification today, embalming is the only method of preserving the dead. A small cut is made in the jugular vein and the blood of the deceased is drained and then replaced with a chemical cocktail that preserves a lifelike appearance. The body can then be worked on by morticians with special sprays and cosmetics that give the corpse the appearance of someone in a deep sleep. In some cases the embalming is performed for a short viewing, but in others the intention is to provide a Lenin-style permanent memorial. Dr Pedro Ara was an Argentinian embalmer known for his use of glycerine rather than the usual formaldehyde, and his work on former first lady Eva Peron was truly stunning. In the Catholic Church there is a slight complication with bodies remaining "incorrupt." Whenever the cause of sainthood is opened for an individual, their body is exhumed. If it has not decayed or decomposed, this is taken to be a sign of sanctity. If one has been embalmed, it is impossible to tell.

It's for this reason that the late Pope John Paul II (pictured at left) was not embalmed, though as he lay on the catafalque it was clear that decomposition was starting. Some of his predecessors were less lucky. Pope Paul VI died during a hot summer, and viewing had to be halted whilst fans were brought in to rid the Lateran Palace of the smell. Pope Pius XII's body was treated by a trainee embalmer who did such a bad job that the lying in state had to be ended early as the Pontiff's body turned black and his nose fell off. The success story is Pope John XXIII (pictured at right), whose perfectly preserved body lies proudly in his glass coffin, which is venerated to this day. Whether embalmed or not, all Popes are carried to St Peter's Basilica where they lie in state in their robes, enabling Catholics to pass by and pay their respects. The College of Cardinals declares the Novendiales, and for 9 days, part of a pre-funeral service takes place. Before the Pope is laid in his coffin, a veil of white silk is placed over his face whilst a red silk bag is placed at his feet, inside which are medals from the Pope's reign and the official notification of the burial. Once the coffin is sealed, it is placed into a coffin of lead before being placed in a third coffin of oak. Recent Popes have all chosen to be buried under marble in the grottoes under the Vatican. It is usual for the next Pope to pay his respects to his predecessor.

It's for this reason that the late Pope John Paul II (pictured at left) was not embalmed, though as he lay on the catafalque it was clear that decomposition was starting. Some of his predecessors were less lucky. Pope Paul VI died during a hot summer, and viewing had to be halted whilst fans were brought in to rid the Lateran Palace of the smell. Pope Pius XII's body was treated by a trainee embalmer who did such a bad job that the lying in state had to be ended early as the Pontiff's body turned black and his nose fell off. The success story is Pope John XXIII (pictured at right), whose perfectly preserved body lies proudly in his glass coffin, which is venerated to this day. Whether embalmed or not, all Popes are carried to St Peter's Basilica where they lie in state in their robes, enabling Catholics to pass by and pay their respects. The College of Cardinals declares the Novendiales, and for 9 days, part of a pre-funeral service takes place. Before the Pope is laid in his coffin, a veil of white silk is placed over his face whilst a red silk bag is placed at his feet, inside which are medals from the Pope's reign and the official notification of the burial. Once the coffin is sealed, it is placed into a coffin of lead before being placed in a third coffin of oak. Recent Popes have all chosen to be buried under marble in the grottoes under the Vatican. It is usual for the next Pope to pay his respects to his predecessor.

Kings and Queens

Death has many forms of course, and it would be saccharine in the very best Rodgers and Hammerstein style to suggest that Royalty always keel over politely without complaint. So drawn out was Charles II's death that he had time not only to beg his brother James to "let not poor Nelly [Nell Gwynn, one of his many mistresses] starve" but to apologise for taking so long to fall off the kingly perch. Queen Victoria was a trendsetter in her attitude to death; Victorian England was famous for rituals and traditions connected with deaths and funerals. Victoria was distraught by the death of her beloved Prince Albert; she wailed so loudly when he was pronounced dead that her screams could be heard all over Windsor. In the wedding photographs of Edward Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra of Denmark in 1863, a pale-faced Victoria can be seen looking up adoringly at a marble bust of Prince Albert as if he had never been gone, and a portrait of the late Prince Consort was included in almost every family photograph taken after he died in 1861. Such was her love for him that memorials cropped up all over London, and when she died, she was dressed in a white dress with her wedding veil, choosing to depart as the corpse bride of a Saxe-Coburg-Gotha rather than a grand old Empress of India. Queen Amelia of Portugal (pictured above), on the other hand, chose to be buried in the blood-stained dress that she had been wearing half a century earlier on the day when her husband King Carlos I and her elder son Prince Luis Felipe were assassinated in front of her. Of course, everything we know about the departure of our favourite royals is pretty much heresay. The only British monarch to die with members of the public present was Charles I, who was executed for treason, and instead of bowing their heads silently, the onlookers rushed up to the scaffold to dip their handkerchiefs into the blood gushing from the King's headless body. However, Charles I did get a proper burial.

Death has many forms of course, and it would be saccharine in the very best Rodgers and Hammerstein style to suggest that Royalty always keel over politely without complaint. So drawn out was Charles II's death that he had time not only to beg his brother James to "let not poor Nelly [Nell Gwynn, one of his many mistresses] starve" but to apologise for taking so long to fall off the kingly perch. Queen Victoria was a trendsetter in her attitude to death; Victorian England was famous for rituals and traditions connected with deaths and funerals. Victoria was distraught by the death of her beloved Prince Albert; she wailed so loudly when he was pronounced dead that her screams could be heard all over Windsor. In the wedding photographs of Edward Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra of Denmark in 1863, a pale-faced Victoria can be seen looking up adoringly at a marble bust of Prince Albert as if he had never been gone, and a portrait of the late Prince Consort was included in almost every family photograph taken after he died in 1861. Such was her love for him that memorials cropped up all over London, and when she died, she was dressed in a white dress with her wedding veil, choosing to depart as the corpse bride of a Saxe-Coburg-Gotha rather than a grand old Empress of India. Queen Amelia of Portugal (pictured above), on the other hand, chose to be buried in the blood-stained dress that she had been wearing half a century earlier on the day when her husband King Carlos I and her elder son Prince Luis Felipe were assassinated in front of her. Of course, everything we know about the departure of our favourite royals is pretty much heresay. The only British monarch to die with members of the public present was Charles I, who was executed for treason, and instead of bowing their heads silently, the onlookers rushed up to the scaffold to dip their handkerchiefs into the blood gushing from the King's headless body. However, Charles I did get a proper burial.

Whilst the lucky ones get to prepare for death, it’s the living who are perhaps most inconvenienced. There’s the matter of honours, hats, orders of precedence, and floral tributes, and then there’s the surreal custom of court mourning. In Britain, royals constantly travel with an appropriately sombre outfit so that if a member of the family kicks the silver-plated ice bucket, they can arrive on home turf suitably attired with a “How sad” expression. This was seen very genuinely in 1952 when Elizabeth set foot in England for the first time as Queen. Lady Pamela Hicks was with her and recalls how, noting the black Daimlers prepared to take the black-clad Royals to Buckingham Palace, the Queen remarked sadly, “Oh, they’ve sent the hearses”. She was greeted by the Prime Minister, a custom that was seen most recently when the body of Diana, Princess of Wales, was flown from France to Britain.

The death of a royal has its timeline. Once the family has said a personal farewell and the Royal Coroner has confirmed the death and issued the death certificate, the public are informed. Recently, this has taken two forms: the more traditional announcement affixed on the gates of Buckingham Palace coupled with a similar announcement to the media. Then begins the complex blend of religious and secular, ceremonial and personal events that form the entire package of regal demise.

If the deceased was a reigning monarch, then his death has to be announced and the accession of the new monarch announced in which the late King or Queen is referred as to as being of blessed and glorious memory, now called to mercy. Of course, those who abdicate are not accorded this right, and the Duke of Windsor’s death was simply announced in the usual way befitting a Prince of the Realm. The first act of any monarch who comes to the throne in the natural way, therefore, is to lead the family, the court, and the nation in mourning, though most of the decisions are made by the Lord Chamberlain. The first thing that has to be decided is how long the court should mourn. When Prince Ernst, Duke of York and Albany, died in 1728, it was announced in the British Gazetteer, “The court mourning for the death of His Royal Highness the Duke of York is to be as follows, viz. The gentlemen to wear coats fully trimm’d, black buckles, black swords and plain linen; and the ladies to wear black, white or grey silks, lawn, cambric or muslin linen fring’d with black and white fans; the mourning to follow three months from tomorrow.” The two most recent deaths of senior royals, Princess Margaret and the Queen Mother, were followed by court mourning that continued until the funeral. During court mourning these days, all official engagements are cancelled, but this hasn’t always been the case. In 1910 Britain saw “Black Ascot,” when high society managed to pull itself out of grief over the death of Edward VII (pictured above) to attend the races. The dress code was formal but funereal and would inspire Cecil Beaton’s designs for the costumes seen in the Ascot scene of My Fair Lady.

If the deceased was a reigning monarch, then his death has to be announced and the accession of the new monarch announced in which the late King or Queen is referred as to as being of blessed and glorious memory, now called to mercy. Of course, those who abdicate are not accorded this right, and the Duke of Windsor’s death was simply announced in the usual way befitting a Prince of the Realm. The first act of any monarch who comes to the throne in the natural way, therefore, is to lead the family, the court, and the nation in mourning, though most of the decisions are made by the Lord Chamberlain. The first thing that has to be decided is how long the court should mourn. When Prince Ernst, Duke of York and Albany, died in 1728, it was announced in the British Gazetteer, “The court mourning for the death of His Royal Highness the Duke of York is to be as follows, viz. The gentlemen to wear coats fully trimm’d, black buckles, black swords and plain linen; and the ladies to wear black, white or grey silks, lawn, cambric or muslin linen fring’d with black and white fans; the mourning to follow three months from tomorrow.” The two most recent deaths of senior royals, Princess Margaret and the Queen Mother, were followed by court mourning that continued until the funeral. During court mourning these days, all official engagements are cancelled, but this hasn’t always been the case. In 1910 Britain saw “Black Ascot,” when high society managed to pull itself out of grief over the death of Edward VII (pictured above) to attend the races. The dress code was formal but funereal and would inspire Cecil Beaton’s designs for the costumes seen in the Ascot scene of My Fair Lady.

Deaths in royal circles can be inconveniently timed, and it has been suggested that Queen Mary’s exit was brought on a little to ensure that court mourning wouldn’t interfere with Elizabeth II's coronation plans, but there is only hearsay and supposition to support this theory. Having said that, there is no doubt that George V’s life was cut short by his doctor. Lord Dawson noted in his diary, "At about 11 o'clock it was evident that the last stage might endure for many hours, unknown to the patient but little comporting with the dignity and serenity which he so richly merited and which demanded a brief final scene. Hours of waiting just for the mechanical end when all that is really life has departed only exhausts the onlookers and keeps them so strained that they cannot avail themselves of the solace of thought, communion or prayer. I therefore decided to determine the end and injected (myself) morphia gr.3/4 and shortly afterwards cocaine gr. 1 into the distended jugular vein. Queen Mary remained calm and kindly throughout." Would Ma'am have done anything else, we wonder? This intervention meant that the King's death occurred early enough to be reported in the more prestigious morning newspapers rather than having to wait for the down-market evening papers. And there have been persistent rumours that George V's elder brother, the unpromising Duke of Clarence, did not die of entirely natural causes but was helped into the hereafter by the administration of poison as he was recovering from flu, allowing the more suitable younger brother to take his place as heir.

Assassination, Suicide, and Murder

There's a lot to be admired in those royals who put themselves in line for the pearly gates when the odds are against them. For example, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Archduchess Sophie (pictured at left) were well aware of the presence of assassins in Serbia when they made their fateful (and fatal) visit to Sarajevo in 1914. Despite suffering a direct bullet to the jugular, the Archduke was heard to plead; "Sophie dear! Sophie dear! Do not die! Stay alive for our children". The pair were transported to the Governor's residence in Konak where they died, with their bodies embalmed and transported to their homeland for public display and mourning. Within a week, trenches that would see millions more follow their lead began to be dug. A similar exit would befall King Carlos I of Portugal who, whilst travelling to his Palace in Lisbon, was assassinated by a revolutionary. His son was mortally wounded, yet his wife Amelia was miraculously unharmed. She died in exile at a ripe old age. As with commoners, suicides are not exactly unknown in crowned circles. Princess Leila of Iran is the most recent case; she checked into the Leonard Hotel in London before taking a lethal concoction of cocaine and quinalbarbitone. She was just 31. At the beginning of the 20th century, Emperor Puyi's mother killed herself in China by swallowing opium. He was said to be totally unmoved by the incident since the two had been kept apart by courtiers for the majority of his formative years. Of course, these were cases of depression rather than romantic suicide pacts such as that rumoured to have been entered into by Rudolf of Austria and his mistress, Baroness Marie Vetsera. Ever so gloriously Black Dahlia, she was shot in the head by her lover before he turned the gun on himself. Their relationship had been the bane of the Hapsburg existence, and their joint suicide was ever so slightly convenient, leading to suspicions about whether the deaths really were self-inflicted.

There's a lot to be admired in those royals who put themselves in line for the pearly gates when the odds are against them. For example, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Archduchess Sophie (pictured at left) were well aware of the presence of assassins in Serbia when they made their fateful (and fatal) visit to Sarajevo in 1914. Despite suffering a direct bullet to the jugular, the Archduke was heard to plead; "Sophie dear! Sophie dear! Do not die! Stay alive for our children". The pair were transported to the Governor's residence in Konak where they died, with their bodies embalmed and transported to their homeland for public display and mourning. Within a week, trenches that would see millions more follow their lead began to be dug. A similar exit would befall King Carlos I of Portugal who, whilst travelling to his Palace in Lisbon, was assassinated by a revolutionary. His son was mortally wounded, yet his wife Amelia was miraculously unharmed. She died in exile at a ripe old age. As with commoners, suicides are not exactly unknown in crowned circles. Princess Leila of Iran is the most recent case; she checked into the Leonard Hotel in London before taking a lethal concoction of cocaine and quinalbarbitone. She was just 31. At the beginning of the 20th century, Emperor Puyi's mother killed herself in China by swallowing opium. He was said to be totally unmoved by the incident since the two had been kept apart by courtiers for the majority of his formative years. Of course, these were cases of depression rather than romantic suicide pacts such as that rumoured to have been entered into by Rudolf of Austria and his mistress, Baroness Marie Vetsera. Ever so gloriously Black Dahlia, she was shot in the head by her lover before he turned the gun on himself. Their relationship had been the bane of the Hapsburg existence, and their joint suicide was ever so slightly convenient, leading to suspicions about whether the deaths really were self-inflicted.

Royal deaths can also inspire commoner deaths. Kiten, Count Nogi, was a Japanese General who was bound by the ancient practice of junshi, requiring servants to commit hara-kiri upon the death of their master. When Emperor Meiji died in 1912, Count and Countess Nogi made preparation for their exit, putting on white kimonos and writing death poems. The two were buried in honour at Aoyama Cemetery.

Murder by one's own royal colleagues is rare, but it's something the world witnessed in 2001 when Crown Prince Dipendra of Nepal decided to massacre his family before attempting to commit suicide. Before finally dying he spent three days in a coma, during which time he was King of Nepal. His actions saw the very popular King Birendra and his Queen, Aiswarya, killed along with two of his siblings and various cousins, aunts and uncles at the Narayanhity Royal Palace. This led to the ascension of King Gyanendra, who has not only proved to be hugely unpopular and absolutist in his manner but has also seen the monarchy in Nepal done away with and has had to leave the palace while a new republican form of government is implemented.